The Protective Barrier: Understanding Traumatic Brain Injury from a Biological, Psychological, and Social Perspective

by Dan Gardner, MD

|

|

|

|

|

|

As an internal medicine intern , I and other trainees evaluated a distraught artist, suffering from shortness of breath and progressive walking problems. Noting a normal physical exam and a recent emotionally traumatic breakup with his lover, I concluded that the symptoms were manifestations of an hysterical conversion reaction, rather than caused by any physical problem. What a shock I had the next day as I observed a swarm of medical personnel rushing this poor man, barely able to breathe, to the intensive care unit to be placed on a ventilator! The diagnosis: polio!

The same year I speculated that a man complaining of severe back pain and a stormy relationship with his son was symbolically expressing his disappointment, frustration, and anger with his son through the pain. That is, his son was "a pain in the back"! I changed my diagnosis, however, after seeing the bone spurs (probably pressing on nerves) in his spinal x-rays.

These two cases are examples of a common pitfall to which we all fall prey at times: the wish to find clear-cut, simple, unambiguous answers to life's complex problems. At the time I was so interested in the psychological factors in illness, that I downplayed possible physical contributors.

As an internal medicine intern , I and other trainees evaluated a distraught artist, suffering from shortness of breath and progressive walking problems. Noting a normal physical exam and a recent emotionally traumatic breakup with his lover, I concluded that the symptoms were manifestations of an hysterical conversion reaction, rather than caused by any physical problem. What a shock I had the next day as I observed a swarm of medical personnel rushing this poor man, barely able to breathe, to the intensive care unit to be placed on a ventilator! The diagnosis: polio!

The same year I speculated that a man complaining of severe back pain and a stormy relationship with his son was symbolically expressing his disappointment, frustration, and anger with his son through the pain. That is, his son was "a pain in the back"! I changed my diagnosis, however, after seeing the bone spurs (probably pressing on nerves) in his spinal x-rays.

These two cases are examples of a common pitfall to which we all fall prey at times: the wish to find clear-cut, simple, unambiguous answers to life's complex problems. At the time I was so interested in the psychological factors in illness, that I downplayed possible physical contributors.

And so it can be in the evaluation and treatment of brain injury. Pressured by constraints of time, money, and other resources, we may eagerly narrow the focus to one particular issue to explain complicated behavior. For example, depending on the perspective of the evaluator, a brain injury survivor's irritability may be attributed only to: frontal lobe bruising, neurotransmitter imbalance, inadequate sleep, poor nutrition, excessive or inadequate medication dose, relationship disappointments, lack of recreational and vocational outlets, loss of job, etc.

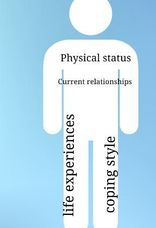

My point is that brain injury is best viewed from a biological / psychological / social perspective: injury occurs to a person with a particular physical status, particular life experiences and coping style, and particular current relationships with individuals and organizations.

My point is that brain injury is best viewed from a biological / psychological / social perspective: injury occurs to a person with a particular physical status, particular life experiences and coping style, and particular current relationships with individuals and organizations.

As a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, I deal with emotional, behavioral, and cognitive problems of head injury survivors and their families. Emotional problems include depression, anxiety, fears, irritability, anger, shame, guilt, etc. Behavioral difficulties include temper outbursts, sleep problems, poor initiative, passive-resistance, impulsivity, wandering, sexual inappropriateness, etc.. Cognitive problems include poor judgment, forgetfulness, poor attention span, trouble with multiple tasks, planning and organizational difficulties, etc.

I find it helpful to view the nature and severity of problems resulting from head injury as determined by a protective barrier (as discussed by neuropsychologist Thomas Kay, Ph.D.) comprised of biological, psychological, and social factors.

And it is individual differences in the components of the protective barrier that explain

why similar neurological insults produce inconsistent outcomes.

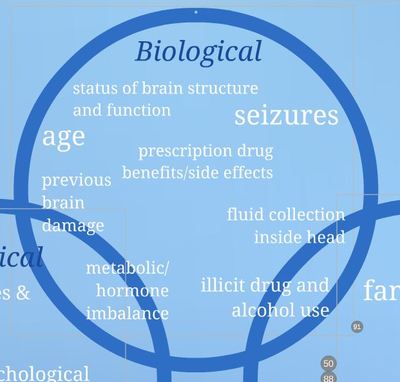

Various biological factors influence outcome in brain injury: for example, status of brain structures and functions, previous head injuries, age, prescription medication effects (benefits and side effects), illicit drug and alcohol use, seizures, fluid collections inside the head, metabolic or hormone imbalance, and infection (inside or outside the central nervous system).

When considering psychological factors, I try to keep in mind the following:

It's not only what happens to us, but how we interpret it

and how we respond to it.

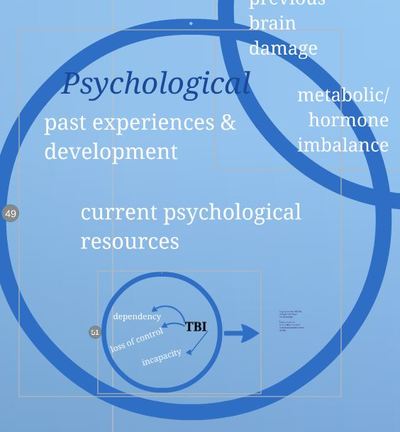

Our psychological vulnerability to brain injury relates to past experiences and development, as well as current psychological resources. We evaluate the present in terms of our past internal psychological conflicts, relationships, and goals.

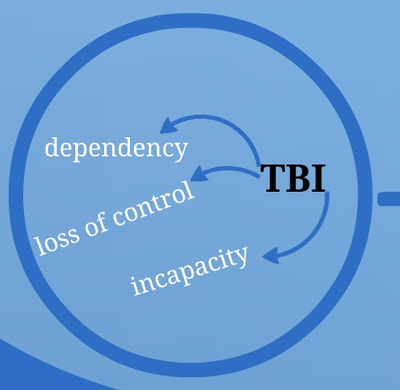

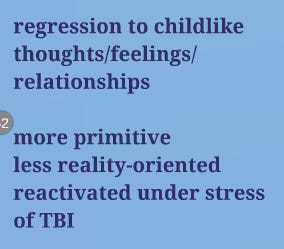

Brain injury and the varying degrees of resulting dependency, loss of control, and incapacity lead to regression, i.e., revival of earlier, more childlike ways of thinking, feeling and relating to others. These are often more primitive and less reality oriented. When healthy, we are unaware of these regressive attitudes ,but they are reactivated and intensified under the stress of head injury.

The regression caused by the head injury reactivates certain universal fears (as described by consultation-liaison psychiatrists James Strain, M.D. and Stanley Grossman, M.D.) that are similar to those we experience at earlier stages in our development.

The ability to adapt to current worries/stresses depends on how adequately we adapted to these stresses when we experienced them as a child. The predominant fears, internal conflicts, and their degree of resolution depends on our early life experiences , e.g., nature of relationships with parents and other caretakers.

Brain injury is always followed by loss of self esteem and unpleasant feelings, e.g., depression, anxiety, guilt, shame, helplessness, powerlessness.

Those of us who as children were not neglected, hurt, or exposed to extreme emotional or physical traumas, and whose relationship with parents was built on trust, are less likely to be affected by the fears, losses and painful feelings of their current disability. For example, a good early childhood relationship with mother allows us to have basic trust in our caretakers. A good early relationship with father leads to our ability to trust men, allow ourselves to be passive in relationships with men (e.g., comply with recommendations of male health care providers and caretakers), and respond to authority without fears of being weak.

Following is a list of the universal fears reactivated by head injury -induced regression. I have illustrated these fears with relevant case examples.

The regression caused by the head injury reactivates certain universal fears (as described by consultation-liaison psychiatrists James Strain, M.D. and Stanley Grossman, M.D.) that are similar to those we experience at earlier stages in our development.

The ability to adapt to current worries/stresses depends on how adequately we adapted to these stresses when we experienced them as a child. The predominant fears, internal conflicts, and their degree of resolution depends on our early life experiences , e.g., nature of relationships with parents and other caretakers.

Brain injury is always followed by loss of self esteem and unpleasant feelings, e.g., depression, anxiety, guilt, shame, helplessness, powerlessness.

Those of us who as children were not neglected, hurt, or exposed to extreme emotional or physical traumas, and whose relationship with parents was built on trust, are less likely to be affected by the fears, losses and painful feelings of their current disability. For example, a good early childhood relationship with mother allows us to have basic trust in our caretakers. A good early relationship with father leads to our ability to trust men, allow ourselves to be passive in relationships with men (e.g., comply with recommendations of male health care providers and caretakers), and respond to authority without fears of being weak.

Following is a list of the universal fears reactivated by head injury -induced regression. I have illustrated these fears with relevant case examples.

Threat to integrity of the self:

Integrity of the self refers to a basic sense of well being, bodily integrity and strength, all of which are "shaken" by a brain injury.

Twenty five year-old John denied the seriousness of his seizures and the existence of post-injury thinking or judgment problems. He boasted of his verbal abilities and of intentions to capitalize on his attractive physical appearance by becoming a male model. At the same time, he avoided social or academic contact with peers, instead preferring solitary exercise activities. The head injury-related threat to his self- integrity added to a prior sense of deep inadequacy , resulting in a defensive, grandiose attitude. The emotional pain of directly acknowledging and dealing with his deficits was intolerable, so he tenaciously clung to a defensive, hyperinflated self- image, which he could only maintain by remaining socially isolated.

Fear of Separation:

Especially common in people with visible, permanent and severe disabilities is the fear of being rejected and abandoned by spouse, children, friends and other family. Often this fear becomes a reality, resulting in despair at the loss of these important relationships. In addition, earlier life experiences of emotional and physical abandonment are reactivated.

Her slow, slurred speech and paralyzed right arm and leg, suffered from a stroke and traumatic brain injury, left Sara in a dependent, incapacitated, and vulnerable position. This reactivated terror, rage and despair stemming from childhood emotional neglect and abandonment by mother while father sexually molested her. The revived feelings resulted in Sara's angry, desperate clinging to hospital staff, as well as to a deep mistrust of and fear of injury by some of her caretakers.

Fear of Loss of Love and Approval:

Jack was despondent over his incapacities: His head injury left him unable to financially support his wife and children, satisfy his wife sexually, and relate patiently to his children. The strong sense of shame and despair Jack currently felt was rooted in his early life failure to win approval from parents who unrealistically expected him as a young child to assume care for his younger sister.

Fear of Loss of Control of Developmentally Achieved Functions:

Control of bowel, bladder, feelings and thoughts may be impaired in brain injuries. The amount of distress over loss of control of these abilities depends on childhood experiences surrounding achievement and loss of control of these functions.

Allen was mortified at the frequent tearful outbursts that followed his head injury. He recalled being shamed by a first grade teacher for wetting his pants and chastised as a child by his parents for any expression of intense emotions.

Fear of Loss of or Injury to Body Parts:

Fears of permanent disabilities may resonate with early childhood fears of injury to and loss of body parts, viewed as punishment and retaliation for desiring an exclusive sexualized relationship with one parent and associated wishes to get rid of the other parent. An injured man may unconsciously view his disability as a symbolic castration, feminization, and subsequent vulnerability to attack by other men.

To cope with a passive, weakened state, which threatened his masculinity, construction worker Bill flirted with women caretakers and boasted to his children about how bravely he endured painful diagnostic procedures.

Feelings of Guilt and Shame and Fear of Retaliation for Previous Transgressions:

Many people view their disabilities as punishment for previous "sins" of omission or commission, e.g., being too needy, greedy, neglectful, disobedient, or hurtful to parents as a child.

Jean believed her accident and injuries were divine retribution for the ingratitude and rage she felt as a child toward her parents, who she experienced as neglectful and depriving.

Tom viewed his head and spine injuries as punishment for an accident he had caused ten years earlier. While drunk, he drove his car broadside into a police car, injuring the officers.

Many people view their disabilities as punishment for previous "sins" of omission or commission, e.g., being too needy, greedy, neglectful, disobedient, or hurtful to parents as a child.

Jean believed her accident and injuries were divine retribution for the ingratitude and rage she felt as a child toward her parents, who she experienced as neglectful and depriving.

Tom viewed his head and spine injuries as punishment for an accident he had caused ten years earlier. While drunk, he drove his car broadside into a police car, injuring the officers.

Personality Style:

In addition to reactivation of universal fears, personality style is an important psychological contributor to how we interpret and react to the deficits of head injury. Personality style can be defined as our habitual mode of relating to our own wishes and fears, as well as to other people.

Passive dependency was Tim's personality style prior to injury. He strove to find both individuals and organizations who would meet his financial, physical, and emotional needs with minimum expenditure of effort on his part. Injury-related deficits and a large financial settlement served to legitimize and reinforce these behaviors. He delighted in attention from his caretakers, but opposed their attempts to help him assume more responsibilities.

Unable to care for her children after a brain injury, Jane felt depressed, ashamed, and helpless. As the oldest of six children, Jane had been placed in the role of caretaker and surrogate mother from an early age. To cope with the frustration and disappointment of unmet dependency needs, Jane developed a Pseudo-Independent personality style, becoming a caretaker and rescuer to many people in her life. The head injury-related deficits interfered with her playing the caretaker role, and the financial gain and attention she received from compassionate rehab staff served as a major, though unconscious, obstacle to rapid recovery.

Ed was a logical, orderly, well- organized engineer with a Compulsive ("Too Perfect") personality style. Post-injury anxiety about his cognitive deficits led to a compulsive preoccupation with and charting of the frequency and character of his bowel movements. This was his attempt to feel more in control of his life: if he couldn't control his thinking, he would turn his attention toward another bodily function that could be more easily mastered.

Other personality styles that influence one's response to head injury are: Histrionic (overly dramatic), Borderline (emotional instability, stormy relationships), and Narcissistic (basic low self-worth hidden by an inflated sense of self-importance).

In addition to reactivation of universal fears, personality style is an important psychological contributor to how we interpret and react to the deficits of head injury. Personality style can be defined as our habitual mode of relating to our own wishes and fears, as well as to other people.

Passive dependency was Tim's personality style prior to injury. He strove to find both individuals and organizations who would meet his financial, physical, and emotional needs with minimum expenditure of effort on his part. Injury-related deficits and a large financial settlement served to legitimize and reinforce these behaviors. He delighted in attention from his caretakers, but opposed their attempts to help him assume more responsibilities.

Unable to care for her children after a brain injury, Jane felt depressed, ashamed, and helpless. As the oldest of six children, Jane had been placed in the role of caretaker and surrogate mother from an early age. To cope with the frustration and disappointment of unmet dependency needs, Jane developed a Pseudo-Independent personality style, becoming a caretaker and rescuer to many people in her life. The head injury-related deficits interfered with her playing the caretaker role, and the financial gain and attention she received from compassionate rehab staff served as a major, though unconscious, obstacle to rapid recovery.

Ed was a logical, orderly, well- organized engineer with a Compulsive ("Too Perfect") personality style. Post-injury anxiety about his cognitive deficits led to a compulsive preoccupation with and charting of the frequency and character of his bowel movements. This was his attempt to feel more in control of his life: if he couldn't control his thinking, he would turn his attention toward another bodily function that could be more easily mastered.

Other personality styles that influence one's response to head injury are: Histrionic (overly dramatic), Borderline (emotional instability, stormy relationships), and Narcissistic (basic low self-worth hidden by an inflated sense of self-importance).

Interpersonal (Social) Factors:

Understanding the interplay of biological and psychological factors within a person is helpful, but incomplete, since a person exists not in a vacuum, but a social network. Our lives are interconnected with family, friends, coworkers, as well as work, school, social, and religious organizations. The degree and nature of these connections influence the outcome after head injury.

One (unconscious) motivation of Dorothy's multiple post-injury physical and emotional setbacks was that she could only see her favorite sister while hospitalized, since Dorothy's husband had forbidden the sister to see her any other time.

Bill, a head injured army veteran, managed to emotionally decompensate and be re-hospitalized just often enough to qualify for his Veteran's Administration disability benefits.

Phil was isolated, suspicious, and argumentative prior to his head injury, estranged from ex-wife, child and his parents. His injury -related deficits served only to magnify his premorbid suspiciousness and to widen the rift between him and family.

Thanks to a generous financial settlement and extreme family dedication and commitment, Frank received a comprehensive, home-based rehabilitation program, which resulted in dramatically improved cognitive, emotional, and behavioral function.

It helps to keep in mind that family's response to a head injured member depends on the nature of the relationship prior to the head injury, the special psychological meanings to the family of the survivor's deficits, and the family's coping style.

Susan's husband was a devoted caretaker, bearing with little protest the emotional and physical strain of her brain injury disabilities. His unwavering involvement seemed based on his guilt about her being struck by a car after she had angrily left their car during a heated argument.

Dale's wife had always been quick to act as a caretaker, in part as a reaction to her own unmet dependency needs in childhood. Dale's disabilities led to her self-sacrificing overinvolvement with him. The increased caretaking efforts served to unconsciously defend more vigorously against her own unmet needs, which she was unable to admit to herself and others for fear of disapproval and rejection.

Pam's mother found herself emotionally reserved and irritated with Pam's incapacities and neediness. Her mother had been raised in a religious school where demonstration of strong emotional needs was explicitly discouraged. Therefore she could not tolerate feelings of neediness and dependency in either herself or her children.

Bill's children coped with their fears of his injury-related rage outbursts by unconsciously identifying with this behavior and reacting to his impending outbursts with verbal attacks and provocations of their own. While their pre- emptive assaults helped his children cope with a terrifying situation, it also intensified Bill's sense of inadequacy as a husband and father and his subsequent rage.

To understand and treat brain injury-related disabilities effectively, it helps to look at the components of the "protective barrier" that stand between the force of impact and the brain. As one author stated,

"It's not only the kind of injury that matters, but the kind of head." (C. Symonds c. 1937)

"It's not only the kind of injury that matters, but the kind of head." (C. Symonds c. 1937)

References

- Kay, T: Neuropsychological diagnosis: disentangling the multiple determinants of functional disability after mild traumatic brain injury. In Horn, L. and Zasler, N. (ed): Rehabilitation of post-concussive disorder: Physical medicine and rehabilitation state of the art reviews 1: 109-127, 1992

- Strain, J, Grossman, S: Psychological Care of the Medically Ill: a Primer in Liaison Psychiatry. New York, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1975

Dan Gardner, MD (www.dangardnermd.com) is in the private practice of Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis in Carmel Valley, San Diego, California. He consults on complicated cases of Traumatic Brain Injury and is an expert witness in TBI cases.

He is a Distinguished Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association; Assistant Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, UCSD School of Medicine; former Council Member, San Diego Psychiatric Society, and former member of the Executive Committee of the Board of Directors, San Diego Psychoanalytic Center.

He is currently Medical Director of Hidden Valley Ranch Rehabilitation Services, consultant to Learning Services Escondido, and consultant with Paradigm Management Services. He also serves on the Advisory Board, San Diego Brain Injury Foundation. He was formerly the Medical Director of NeuroCare at Stone Mountain, a post-acute brain injury rehabilitation program in Ramona, CA.