Before We Push Pills: Viewing Traumatic Brain Injury

from a Biological-Psychological-Social Perspective

By Dan Gardner, MD

Nowadays, psychiatrists are often seen as pill pushers. Have some anxiety? There’s a pill for that. Got depression? There’s a pill for that, too. You want long-term psychotherapy for more comprehensive change? Sorry, but managed care won’t cover that!

But isn’t there more to thoughtful diagnosis and treatment than identifying a list of symptoms and prescribing a drug?

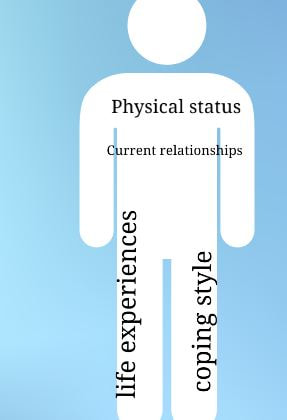

I believe that TBI is best viewed from a biological/psychological/social perspective: injury occurs to a person with a particular physical status, particular life experiences and coping style, and particular current relationships with individuals and organizations.

But isn’t there more to thoughtful diagnosis and treatment than identifying a list of symptoms and prescribing a drug?

I believe that TBI is best viewed from a biological/psychological/social perspective: injury occurs to a person with a particular physical status, particular life experiences and coping style, and particular current relationships with individuals and organizations.

Let’s look at the following example. Secluding himself in the bedroom, darkened to match his gloomy mood, brain injury survivor John stared blankly at the television. His thoughts turning inward, John sighed heavily under the weight of deep, unremitting despair. Shortly after returning home from the hospital, his buddies quit visiting. And hopes of attracting girls were dashed by the confused, suspicious, frightened, and wary reactions of others to his slowed speech and awkward gait.

How do we understand John’s problems after TBI? And how do we help him make the best recovery possible?

In today’s healthcare environment, healthcare providers are increasingly asked to “do more with less” due to limited health care resources. When I first began consulting with patients on a rehabilitation unit, a length of stay of 3- 4 months was common. According to Uniformed Data System for Medical Rehabilitation (accessed 6/11), between 2006 and 2010, the average length of stay in acute rehab for a TBI patient was 17.5 days.

And under this type of pressure, a potential pitfall is for us to take an expedient, narrow view and seek simple, clear explanations and interventions for complex problems.

Isn’t it easier when all we have is a hammer? Then everything is a nail.

For example, depending on how an evaluator conceptualizes John’s problems, his irritability could be viewed through a narrow lens as primarily caused by one of the following factors: depression, impaired memory, inadequate sleep, poor nutrition, excessive or inadequate medication dose, unresolved psychological conflicts, relationship disappointments, blocked flow of energy, pain, impaired mobility, lack of recreational and vocational outlets, loss of job, etc.

But while it is tempting to narrowly focus on simple answers to complicated problems, I believe we need to deal with significant ambiguity and uncertainty in order to identify the multiple causes of and contributing factors to a patient’s problems.

In our understanding and treatment of John’s TBI, wouldn’t it be helpful to have the following biological, psychological and social background information? (The following is not a complete list.)

1. Biological: Is there a history of birth trauma or prior concussions? Did he abuse alcohol or drugs? Does he have diabetes or high blood pressure? Are his medications causing drowsiness or impaired concentration?

2. Psychological. How did John relate to his parents and other authority figures in his childhood? Did he feel safe and cared for or insecure and anxious? How did he cope with having to depend on others? How did he react when he was sick? Wouldn’t this help us understand how John relates to his current caregivers and reacts to his disabilities?

For example, if John was raised in a family with an uninvolved father and emotionally supportive mother, would it make sense for John’s primary caregivers to be women?

If John readily followed directions as a child, would it make sense for his caregivers to be firm and clear in their directions? Or if John was an oppositional child, would it make sense to allow John more choices in his treatments?

What if John was taught by example that masculinity was equivalent to self-sufficiency? Would his disability result in fears of losing close relationships because he could no longer care for himself? How would John handle the frustration and disappointment of not having a girlfriend? If John had lost a sibling in earlier life, would the current disability re-awaken the distress of his earlier loss, including the guilt of his surviving when his parent/ sibling did not?

3. Social: What if John’s primary support group was composed of long-distance bicyclers? Or a chess club? Would his friends continue to visit when impaired mobility or memory prevented John from participating? Would he benefit from the emotional support and education of a brain injury survivor group and a peer-mentoring relationship?

In today’s healthcare climate, we are certainly challenged by the multiple factors interacting to result in our patients’ disabilities. It would be so much easier to take a narrow approach.

But, hopefully, motivated by caring and concern for our patients, we will still find the time and energy to view complex problems through the bio-psycho-social perspective and deliver the best quality of care.

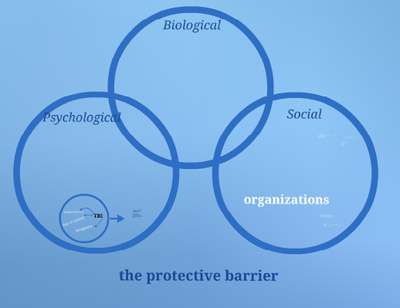

Learn more: read Dr. Gardner's article, The Protective Barrier in Traumatic Brain Injury

Traumatic Brain Injury literature searches

DONATE: San Diego Brain Injury Foundation | Southern Caregiver Resource Center

Traumatic Brain Injury literature searches

DONATE: San Diego Brain Injury Foundation | Southern Caregiver Resource Center